Poetry /

Hafez's yoosofé gom gashté

In this introductory lesson to Hafez's poem yoosofé gom gashté, we're joined by Prof. Sahba Shayani to talk about the general theme and meaning behind this poem.

Watch Now

View audio version of the lessonGREETINGS:

hello

سَلام

how are you?

چِطوری؟

Note: In Persian, as in many other languages, there is a formal and an informal way of speaking. We will be covering this in more detail in later lessons. For now, however, chetor-ee is the informal way of asking someone how they are, so it should only be used with people that you are familiar with. hālé shomā chetor-é is the formal expression for ‘how are you.’

Spelling note: In written Persian, words are not capitalized. For this reason, we do not capitalize Persian words written in phonetic English in the guides.

ANSWERS:

I’m well

خوبَم

Pronunciation tip: kh is one of two unique sounds in the Persian language that is not used in the English language. It should be repeated daily until mastered, as it is essential to successfully speak Persian. Listen to the podcast for more information on how to make the sound.

| Persian | English |

|---|---|

| salām | hello |

| chetor-ee | how are you? |

| khoobam | I’m well |

| merci | thank you |

| khayli | very |

| khayli khoobam | I’m very well |

| khoob neestam | I’m not well |

| man | me/I |

| bad neestam | I’m not bad |

| ālee | great |

| chetor-een? | how are you? (formal) |

| hālé shomā chetor-é? | how are you? (formal) |

| hālet chetor-é? | how are you? (informal) |

| khoob-ee? | are you well? (informal) |

| mamnoonam | thank you |

| chetor peesh meeré? | how’s it going? |

| ché khabar? | what’s the news? (what’s up?) |

| testeeeee |

Leyla: salām, sahba jān. Thank you for joining me for another poem together.

Sahba: salām, leylā jān. My absolute pleasure. Thank you for having me.

Leyla: Yes. Wonderful. And today, we are going to be studying a poem by Hafez, which is actually Ghazal number 255. And so this is the entire poem. It's only ten lines. So we're going to study the whole thing. So before we begin, I want to ask you the background of this poem and why we chose it? Let's start there.

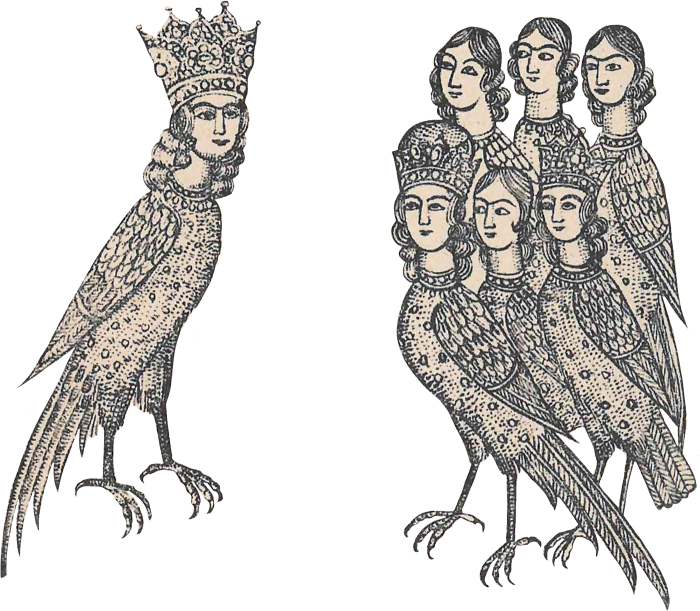

Sahba: Okay. We chose this poem because, well, it is one of Hafez's most renowned poems. And the message behind it is just absolutely beautiful. And the imagery that he uses is all imagery rooted, or much of it is imagery rooted in the traditions of the Old Testament and then adopted in the Qur’an. So it's a very unifying and beautiful poem with lots of unifying and beautiful imagery in it. So that's why I thought it would be appropriate. And I think the message that it really bears is something that I think everyone can benefit from and really enjoy. So it's a good one to memorize, even if you have a few lines of it memorized, something to have as a mantra almost that you can recite to yourself sometimes.

Leyla: Interesting. So then, I'm not familiar with this poem, so I've only just glanced over it. I'll be learning along with the students as we go over it, but I do notice a lot of very direct religious references, which is interesting because all the Hafez poems that we've covered so far, they're ambiguous. You could read them in a religious manner, but everything's coded. In this poem, it seems like he's very explicit. And he even mentions the Qur’an, he mentions different people of religious figures. Can you talk a little bit about that? Is this a very explicitly Islamic poem?

Sahba: I wouldn't say it's explicitly Islamic, to be honest. I mean, other than the mention of the Ka‘beh and the Qur’an, and even in that case, the Ka‘beh is the house of God, and Qur’an is the holy book. But I mean, it is, but obviously, the story that it references, the story of Joseph, is a story that we get from the Torah and the Old Testament. So it's one that really brings these traditions together. And, in the Islamic tradition that they build upon one another, you know, Judaism and then Christianity and then Islam, it does have an Islamic element to it, naturally. But it has, I would say, like an Abrahamic element to it, but definitely a very clear religious element to it that draws on all the traditions and brings them together. And it is, in true Hafez sense, it still uses that similar energy of like, just religious or like spirituality, to bring it all together in a way, rather than just explicitly I think one religion.

Leyla: So do you need to be religious in order to understand it or to enjoy it, or to get anything out of the poem?

Sahba: I don't think so. No, I think the idea is, the idea behind the poem itself is beyond religious in a sense, but it is spiritual. Definitely, there is an element there that we connect to a higher source.

Leyla: Okay, interesting. I'm excited to go over it. But now to back up a little bit, can you tell me who, if anyone is listening, and they don't know who Hafez is or if we need a little bit of a refresher, who is Hafez in general, and what is a “ghazal?”

Sahba: Okay. Hafez Shirazi is a 14th century poet, arguably the poet par excellence of Persian poetry. Definitely from the Iranian perspective, and from the canonized modern perspective that we have, Hafez is seen as one of our greatest, if not our greatest poet and the master of the ghazal. Ghazal poetry is love lyric poetry. They're usually shorter poems that focus on the topic of love. And this love can be physical, or it can be divine. And often there's an interplay between the two where you can't really tell which is which. In this case, very clearly, there's a divine element to it, like you said, with the references to the Qur’an and to the stories from the Old Testament. And yeah, he is, I mean, he is a poet that every Iranian practically has a line here or there memorized by him, at the very least, if not poems fully. You can't escape Hafez as an Iranian, I think, his divān, his compilation of poetry, is what we put on the haft seen often, it's what we put on our shabé yaldā spreads, It's what we use for bibliomancy, which is the tradition of trying to tell fortune through, like, opening up certain parts and like, making and setting an intention and opening a certain part of the book and reading to see what Hafez responds to you with. He’s known as “lisān-ol-gheyb,” which means ‘the tongue of the invisible.’ So there is this concept, this notion that he had this or still has, in a way, in his essence, this connection to the beyond, to that which lies beyond what we can see in this world. And so, therefore, Iranians often turn to him for answers. So let's say you're stuck with something, you set an intention, you take the book, and you just open whatever page you're drawn to opening with your eyes closed, and then you go back and read the poem that ends, you read that poem from the beginning. You read from the beginning of the poem. And he's believed to respond to your intention, to your question, to your “neeyat,” as we call it.

Leyla: I'd never heard that word, ‘bibliomancy,’ that's what that means?

Sahba: Yes, bibliomancy. Yeah, like “fāl” with a book.

Leyla: Interesting. Okay. And then that “lisān-ol-gheyb,” is that the same that is in Dune? Is that right? Am I remembering that correctly?

Sahba: Yes, yes, yes, yes, yes.

Leyla: Okay, so it is referring to, is Hafez the only person that is called that in history? Are they referencing Hafez?

Sahba: Yeah, yeah, to my knowledge, he's the only poet who we refer to as “lisān-ol-gheyb.”

Leyla: Amazing. So what gives him that, like, who was he writing these poems for? And what was his religious background?

Sahba: So I mean, obviously, he was Muslim himself. He most likely he was Sunni, as were many of our traditional poets from the Persian canon, at least prior to the Safavid period. He’s called Hafez because he had the Qur’an memorized. So a person who would have the Qur’an memorized would be called a Hafez, someone who protects or remembers. And to be honest, I think maybe the reason he is called “lisān-ol-gheyb” is because of the fact that he has the Qur’an memorized, and he's seen sort of as this protector of the holy text. But his poetry is fantastic in the sense that, I mean, like you said, like you mentioned yourself earlier, it's at this intersection and interplay between religious and like, explicitly religious and then implicitly sort of religious or spiritual and actually in his poetry, he often reprimands the religious figures, the sheikh, you know, the sheikh and these individuals who are seen as staunchly religious figures who go by the book aren't necessarily seen as positive characters. And the positive character is the character whose heart is pure and who walks on the path of God for the sake of the love of God, not for the sake of following every single code, and so on and so forth. So he uses a lot of wine imagery in his poetry. The tavern is often seen as his place of worship. So there's a lot of breaking of the traditional religious concepts and images.

Leyla: And then for you personally, what has been your relationship with Hafez? Where did he enter your life, and where did you start to become interested in his poetry?

Sahba: Okay, so I need oh, God, that's a difficult- I feel like Hafez has always been there, sort of, I personally, this is going to be a hot take.

Leyla: Okay. Oh, good!

Sahba: Hafez is not my necessarily favorite poet of all time. I'm much more drawn to the ghazals of Rumi, Jalaluddin Maulana. Those ghazals are the ones that really speak to me. But out of Hafez’s ghazals, this is one of the ones that I'm definitely drawn to, and it's one of my favorites. But Hafez, there's no denying that Hafez is the master ghazal composer. His ghazals are the most beautiful, the most intricate, and they're really, in one of his ghazals, he says, you know, that it's like he strings pearls one to another and creates this beautiful necklace. And it's very true, because a lot of times the lines in the ghazal are related, but they're not explicitly related. And you have to try to find the notes between them, but they sort of do become like these pearls of wisdom, each line that you string together to create this beautiful necklace, this beautiful ghazal.

Leyla: And can you place us where he was in relation to Rumi, in time and just what type of writer he was?

Sahba: So he's writing in the 14th century. He's similar to Rumi in that there is a heavy mystical undertone in his poetry. Rumi, I think traditionally is seen, to some extent, to be more by the book, whereas Hafez is seen to be sort of more implicitly religious or spiritual and sort of trying to break away from the tradition of what is written. But they're both in the tradition of the mystical, of the mystical writers. From Hafez, what we really focus on are his “ghazaliyāt,” his ‘love lyrics.’ Maulana, the depth of poetry and the vastness of it, I would argue, is more. And it's really like his “ghazaliyāt” are very renowned. But what's much more famous from Rumi's poetry is his masnavi, masnavi-ye ma’navi, which is a long poem, and it's a story, essentially. That is a story within a story, within a story, it's called the Persian Qur’an, the masnavi-ye ma’navi. So it's seen as this almost holy-like text. So it's different. His writings are different, quite different from that of Rumi, but both their focal point is mystical in essence.

Leyla: And how do you feel about, like reading, Hafez has been famously, infamously, translated by, for example, Coleman Barks. There are these interpretive translations of it. How do you feel about, first of all, those translations or just in general, reading translations of Hafez's work versus reading them in their original?

Sahba: I'm very against translations that take a lot of liberties. Yeah. I think you can't really call something ‘the poetry of,’ and this is done with Rumi, actually, more than anyone, but you can't call something ‘the poetry of Rumi’ or ‘the poetry of Hafez,’ when you just write something that you're “inspired,” quote unquote, by the poet and then call it their poetry, you know, it's not right. You have to, there are elements that should be kept, and there's a lot of talk about this, actually, about how the poetry of Rumi and the poetry of Hafez, but particularly Rumi, is stripped of its origin, of its Muslim identity. And, again, I would argue that a lot of these, there's a Muslim identity, but they link to all of these religious traditions through them, because Islam is related to Christianity and Judaism. So it's one that builds on all of these traditions. So it's not like it's just Muslim or just for Muslims. But it is, the roots of it are in the Islamic and the Abrahamic traditions. So when you when you strip it of that and you just turn it into something, you know, completely different, it's not right. But particularly my problem with it is in translation. When you translate the poetry of someone, you should try to keep it as close as possible to the original essence of the poem itself, not create something yourself and say it was inspired by it. Now, the other side of it is that, well, a lot of times, direct translations may not be as attractive or appealing to the eyes, especially of those who are not familiar with the tradition. And so then you get into this gray area of like, okay, well, what's the right balance? What's the best way of doing it? And that's a, you know, it's a difficult question to answer. Nothing's black and white, essentially. But my, and you'll see with my translation, I try to not take liberties as much as possible when I can, when I can stick to the original, I try my best to do that, because I want the reader to really get, for it to be to them as if they're reading the original Persian, you know, to get the imagery, even the word order that Hafez or Moulana or whoever the poet is, is using.

Leyla: But as skilled a translator as you are, I'm sure that nothing compares ever, ever, ever.

Sahba: Thank you. I mean, yeah, no, exactly. Yeah, nobody's translation can compare ever. Yeah, exactly. It's just an idea of like how close can you get it, you know. And yeah, exactly, exactly. And my translations are flawed in their own ways, I'm sure. But there are a lot of people, you know, a lot of people have written on Hafez. And I think it's important to turn to scholars, individuals who have actually spent their lives and their time on working on the poetry of these individuals. And, for Hafez, someone who I can always recommend to listeners is the work of Dominic Parviz Brookshaw, Professor of Persian Literature at the University of Oxford. His specialty has been Hafez. And so if you're interested in a book, check out his writings.

Leyla: Absolutely. And yeah, I commend everybody for listening to these because again, this might, when you first encounter Hafez, even, you know, as someone who is in the diaspora, and isn't, you know, in Iran, when you first encounter the works of Hafez, it sounds very foreign. It sounds very challenging. But we have to remember that, like you said, it's ubiquitous in Iran. From the time you're a baby, you're hearing these verses, you're hearing these words, and it just becomes a part of your everyday language. And so I commend everyone for listening to this. You know, what we're trying to do with this program is to make it accessible for everybody, because there are some key elements. It's just like Shakespeare, you know, when you first hear it, even if you're a native English speaker, some things might seem unfamiliar to you. But once you unlock those key elements, it becomes more and more familiar. So that's why, you know, this lesson is accessible, even to complete beginners of the Persian language, because you might even be a little two-year-old in Iran hearing these poems. And you become familiar with them. It becomes a part of your everyday vocabulary.

Sahba: And I think, you know, a big part of our ability to become more worldly and to learn more about the world around us is by exposing ourselves to things that or to, you know, concepts and elements and poetry and writings that aren't, you know, as familiar to us. And I think you see this in Europe a lot. People are much more keen to reading, you know, books by a Japanese author or like a, you know, Nigerian author or someone that is something different. And I think that's something that in the States, I hope we do more and more too, because even if it doesn't resonate with you initially, the more you get used to it, the more you realize the beauty in it, the more you learn, you know, and the more worldly you become.

Leyla: Absolutely. Well, cool. Well, I'm excited to get into this poem. And as we do every time, this time Sahba and I will be going through the poem generally. So this is the first time you'll be hearing it. So don't be afraid if you don't understand any of the words, but he'll be reading the Persian, and I'll be following with his translation, in English. And then after this lesson, I will have a series of individual lessons. There’ll be five more lessons where, in each lesson, I'll go over two of the lines and we'll go over each and every word and phrase in the poem and learn how to use it in conversational Persian, so that you can use these words in your everyday speech. And, we will have a selection of this poem for you to memorize and make a video for us in a beautiful location, reciting these words. And it's so wonderful that this poem, you know, speaks to Sahba in a way. And by memorizing it, hopefully it will speak to you personally. And you can relate it to yourself, whether you are religious, not religious or anything that you are. I think that we’ll all be able to learn a lot.

Sahba: You don't have to be religious in any way. It's a poem that really draws on that for everyone.

Leyla: Perfect, and after we read it, I want to talk about this bibliomancy and what this could tell us about our lives, if this was the poem that we would have chosen randomly out of the Hafez book. So this is ghazal number 255. Are we ready to dive in? Or any other last thoughts that people should have before we dive in?

Sahba: No, I think we covered quite a bit.

Leyla: All right, all right, here we go, ghazal number 255.

Sahba: yoosofé gom gashté bāz āyad bé kan'ān, gham makhor! kolbéyé ahzān shavad roozee golestān, gham makhor!

Leyla: The lost Joseph will again return to Canaan; grieve not! The House of Sorrows will someday become a rose garden; grieve not!

Sahba: ay delé ghamdeedé, hālet beh shavad, del bad makon! v'een saré shooreedé bāz āyad bé sāmān, gham makhor!

Leyla: o afflicted heart, you’ll feel better; despair not! And this disheveled mind will again find respite; grieve not!

Sahba: gar bahāré omr bāshad bāz bar takhté chaman chatré gol dar sar kashee, ay morghé khoshkhān, gham makhor!

Leyla: Should the spring of life repose again upon the throne of green you’ll raise a canopy of roses over your head, o sweet-singing bird; grieve not!

Sahba: doré gardoon gar dō roozee bar morādé mā naraft dā'eman yeksān nabāshad hālé dorān, gham makhor!

Leyla: Should the heavens not turn in our favor for a couple of days the ways of the world never remain the same—grieve not!

Sahba: hān mashō nomeed chon vāghef nay-ee az seré ghayb bāshad andar pardé bāzee-hāyé penhān, gham makhor!

Leyla: verily, do not dismay that you are not privy to the secrets of the invisible (for) behind the veil lies many a secret game; grieve not!

Sahba: ay del, ar saylé fanā bonyādé hastee bar kanad chon tō-rā nooh ast kashteebān, zé toofān gham makhor!

Leyla: o heart, should the flood of annihilation uproot the very essence of existence so long as Noah is your captain, from the storm grieve not!

Sahba: dar beeyābān gar bé shoghé ka'bé khāhee zad ghadam sarzanesh-hā gar konad khāré moghaylān, gham makhor!

Leyla: if you cross the desert in longing for the House of God should the Egyptian thorn reproach you, grieve not!

Sahba: garché manzel bas khatarnāk ast ō maghsad bas ba'eed heech rāhee neest, k'ān-rā neest pāyān, gham makhor!

Leyla: though the route is quite dangerous and the destination quite far there is no road that has no end; grieve not!

Sahba: hālé mā dar ferghaté jānān ō ebrāmé ragheeb jomlé meedānad khodāyé hālgardān, gham makhor!

Leyla: our condition in separation from the beloved and the torments of our rivals is all known to the Lord who alters conditions; grieve not!

Sahba: hāfezā, dar konjé faghr ō khelvaté shab-hāyé tār tā bovad verdat do'ā vō dars ghor'ān, gham makhor!

Leyla: o Hafez, in the corners of poverty and the loneliness of dark nights so long as your mantra is prayer and your guide the Qur’an, grieve not!

Leyla: All right, amazing!

Sahba: It's beautiful, isn’t it? I love it.

Leyla: It is beautiful.

Sahba: I love this poem.

Leyla: Wonderful. But yeah, I see a lot here for us to dive into. So I'm excited. Now we're going to go over it from the beginning. Sahba will lead the way. But before we begin, I want to start with what we hear most of all in the entire poem. And that is, “gham makhor!” So let's start with that. You have translated it as ‘grieve not,’ but can you expand on that? What is “gham makhor?”

Sahab: So “gham” is ‘sorrow,’ ‘grief’. And in Persian, it’s actually a beautiful verb. ‘To grieve,’ ‘to be sad,’ one of the ways of saying it is “gham khordan,” ‘to eat sorrow,’ ‘to eat grief.’ And so when he says “gham makhor,” he's negating it in the imperative. He's saying, do not, literally, ‘do not eat grief.’ But what it means is, do not grieve, do not sorrow. Don't be sad.

Leyla: Well, one question that I have about that is “khordan” could be two different meanings, right? Like “khordan” like “zameen khordam,” like the ground hit me, or it could mean eating. So in this case, you're saying it means you're ingesting sorrow, or it's hitting you?

Sahba: No, “khordan” than just means ‘to eat.’ So literally “zameen khordam” also means to eat the ground. Literally. But it's how we use it, you know, it's like you actually fall to the ground or hit to the ground. So in this case too, it’s the same idea. I mean, when someone says “gham makhor,” you don't necessarily think of it in the concept of eating at all, it's in the sense of like, you know, grieving. But the way that we compound the verb is with the verbal element of “khordan,” ‘to eat.’

Leyla: That is really nice. So don’t eat sorrow.

Sahba: And in a way, with sorrow, it makes sense. With sorrow, it makes sense. Like you said, you're ingesting it. Yeah.

Leyla: So then also when we're speaking, we would say like “nakhor.” Is “makhor” the same thing as “nakhor?” ‘Do not eat.’

Sahba: Yeah, it is. “makhor” is the same as “nakhor.” It's a more poetic version of it.

Leyla: All right. Yeah. So that's one thing then with poetry, we have to realize like some words just have a poetic version. But in, you know, in conversational, everyday speak, that's not how we would just say, like, “gham nakhor.” That's something that we would say.

Sahba: Yeah, yeah, yeah, exactly. There are other phrases that we use the “ma” instead of the “na” in too, but it does have a more archaic sort of poetic element to it.

Leyla: Yeah. Well, it's a really nice, I just wanted to pause on that since we see it so much. It's just like, the structure of the poem seems to be this is happening, this is happening, do not feel sorry. Don't get like, don't get engulfed by sorrow is how I'm seeing it. Don't get engulfed by sorrow. All right, so let's take it from the top.

Sahba: Okay. “yoosofé gom gashté bāz āyad bé kan'ān, gham makhor! kolbéyé ahzān shavad roozee golestān, gham makhor!” So the first, in the first hemistich, you see, ‘the lost Joseph will return to Canaan; grieve not!’ So this immediately goes back to the story from the Old Testament. And then again, what is known in the Qur’an as Ahsan al-Qasas, the best of stories, which is the story of Joseph. So immediately, you have this Quranic Old Testament reference right there that is familiar to Hafez’s audience, as it is to people in Iran today. It's the story of the Prophet Joseph, who’s known to be the most beautiful of men. He's the paragon of beauty in a lot of, in the religious traditions and the poetic traditions, the paragon of beauty and also a paragon of chastity. So it's in reference to Joseph, whose brothers, out of jealousy, take him to the desert one day and throw him into a well, and then go to their father, who favored Joseph more than any of his sons, and tell him that Joseph has died. And as a result of this, the house of Jacob, who's the father of Joseph, turns into the House of sorrows, and Jacob loses his eyesight out of crying and crying and crying for his beloved son Joseph. But what happens at the end of the story, spoiler alert, is that Joseph isn't killed, actually. And he's sold as a slave to Egypt, and he's brought from the land of Canaan, which is what Hafez is referring to here, is the homeland of Joseph. He becomes a slave in Egypt, and eventually he rises up the ranks and becomes a sort of like a minister in Egypt. And as a result, during the famine, his brothers return to come to Egypt, seeking food. And they encounter Joseph, without knowing that it’s Joseph, and Joseph sends his garb to them to give to his father, and his father receives this garb, and the scent of the garb revives Jacob's eyesight, and then they're eventually reunited. So Joseph returns. So it's all in play of this story. So he's saying, “yoosofé gom gashté bāz āyad bé kan'ān,” ‘the lost Joseph shall return to Canaan, as he does in this tradition.’ “gham makhor!” ‘Fear not!’ “kolbéyé ahzān,” ‘the House of sorrows,’ which is the House of Jacob, Joseph's father, “shavad roozee golestān,” ‘will one day become a rose garden.’ “gham makhor!” ‘Fear not’ or ‘sorrow not.’ Next line: “ay delé ghamdeedé, hālet beh shavad, del bad makon!” o heart that has “ghamdeedé,” that has seen sorrow, literally, right. That has experienced sorrow. “hālet beh shavad,” and this is something we commonly, “hālet behtar meeshé,” “hālet beh shavad,” ‘your state will become better.’ “del bad makon,” ‘don't sully your heart,’ don't make your heart or your state or your hearts dirty, literally. Don't make your heart bad, but don't sully your heart. “v’een” is just “va een.” “v’een,” “va een,” “saré shooreedé,” and this tumultuous head, this head that’s sort of spiraling, “bāz āyad bé sāmān,” ‘it'll return again to tranquility,’ to “sāmān.” “gham makhor!” I think this hemistich is something we can all connect with in this day and age. You know, when we're doomscrolling and sort of spiraling in our own world, saying it'll be okay. It'll come back to its tranquility. Fear not. “gar bahāré omr bāshad bāz bar takhté chaman,” So, if the spring of life, if the spring of the expanse of our life, our life span, bāshad bāz bar takhté chaman, if it again is, I translated it as if it sits again or reposes again upon the throne of greenery, “takhté chaman,” ‘the throne of grass,’ literally ‘the throne of greenery.’ “chatré gol dar sar kashee,” ‘you'll cover your head with a parasol or a canopy of roses again.’ “ay morghé khoshkhān,” ‘o sweet singing bird, o sweet voiced bird.’ “gham makhor!” ‘Sorrow not!’ And again, these are very common images in classical Persian poetry. The “morghé khoshkhān,” you know, ‘the bird that has a beautiful voice,’ the “omr” being compared to bahār or “khazān,” which is spring or autumn, and the “takhté chaman,” ‘the throne of green,’ which is essentially comparing the garden to the throne in this case. doré gardoon gar dō roozee bar morādé mā naraft. So here he’s playing with words too. “doré gardoon gar dō roozee.” Do you see the sounds are playing with one another? “doré gardoon” So literally the spinning of the heavens of the gardoon, of that which turns. But “dor gardoon gar dō roozee.” See the playing with the “gar” and the “do” sounds that are being used. This is why he's a master of his craft. “doré gardoon gar dō roozee bar morādé mā naraft” So the spinning, you see, this spinning of the heavens. “gar,” “agar,” ‘if,’ “dō roozee,” ‘for two days.’ That's why I said a couple of days, like we say in English. So ‘the spinning of the heavens, if for a couple of days,’ “bar morādé mā naraft.” If it didn't go to our wishes, meaning it didn't spin the way that we had wanted it, meaning what we wanted didn't happen, if for a couple of days, and the couple of days is, you know, much longer than a couple of days.

Leyla: Could be eras, yeah. Yeah, of course.

Sahba: But you know, it's also harkening to the fact that our lives are like quite short, you know, and if for a period of it though, it doesn't go the way you want it to, “dā'eman”-

Leyla: Oh, sorry. I want to point out too, “dō rooz” comes up in Persian poetry a lot, like “donyā dō roozé” ‘the world is two days,’ you know, that comes up often. It's just a couple of days. Like it's so short.

Sahba: Sure, exactly. Yeah, exactly. “dā'eman yeksān nabāshad hālé dorān, gham makhor!” So “dā'eman,” “hameeshé,” ‘always,’ “yeksān nabāshad,” ‘equal won't be,’ ‘it always won't be the same.’ “hālé dorān,” ‘the state of the era,’ ‘the state of time,’ “gham makhor!” So ‘things will never remain the same.’ ‘Don't sorrow.’

Leyla: Isn't that so beautiful? So the imagery is just like the way he's making it seem like you're seeing the spinning of these planets, and like, okay, it's not going the way we want, but then it doesn't stay static. It's spinning. It’s changing.

Sahba: Exactly. It spins. Yeah, yeah. hān mashō nomeed chon vāghef nay-ee az seré ghayb. So “hān” is like ‘verily’, ‘in truth.’ In truth, again, “mashō,” that same “nashō,” “mashō,” the same concept. So do not become, do not be, “nomeed,” “nā omeed.” Do not become hopeless. “chōn,” ‘because,’ “vāghef nay-ee,” ‘because you're not aware,’ “az seré ghayb,” ‘because you're not privy to,’ “seré ghayb,” ‘the secrets of the invisible,’ meaning the secrets of the world beyond. So don't be sad, because you're only confined to the conditions of the human condition. You only know what's going on here. You don't know what's, or not even everything that's going on here. Don't be sad if you don't know what everything that's going on, you don't understand everything. That's essentially what he's saying. Don't be sad if you can't make sense of everything. bāshad andar pardé bāzee-hāyé penhān, gham makhor! Behind the veil, there are hidden games. And this is a very esoteric, mystical concept that you find in the poetry of Khayyam a lot too, which I know you've covered before, too, that there's a lot of games happening behind the veil, meaning in the world beyond, in the realms that are beyond our comprehension and understanding. And in my opinion, it's harkening to the fact that the greater being, the greater source has a way and a means for everything that's happening. You can't understand it. Don't worry. Don't grieve. Our condition as human beings is one where we can't understand everything that happens in the world. Why does it happen? For what reason does it happen? Why me? You know, all of these things. These are not things we're privy to. All we know is that there's a lot going on behind the scene. And the one who's in charge knows what he's doing. Don't worry. ay del, ar saylé fanā bonyādé hastee bar kanad. So “ar” is a shortened form of “agar.” So o heart, if the flood of annihilation, “saylé fanā,” again “fanā” is a very mystical Sufi concept. The concept of becoming nothing, of nothingness, of becoming annihilated, so that you can reach “bahā’,” you can reach eternity in a way. So “ar saylé fanā bonyādé hastee bar kanad” ‘If the flood of annihilation of nothingness uproots the very essence of existence.’ If it even destroys everything that you know to be your reality, your existence, “chon tō-rā nooh ast kashteebān,” as long as Noah is your-

Leyla: Captain.

Sahba: What do you call it in English? Your captain, thank you. ‘As long as Noah is your captain, is the captain of your ship, is the one steering your ship,’ “zé toofān,” ‘from the storm,’ “gham makhor!” ‘Grieve not,’ grieve not because of the storm. Why? Because you're in good hands. It's going to be okay. You're in the hands of one who is inspired by the divine. And this is why I'm saying it keeps connecting to these traditions of obviously Islamic traditions that are rooted in the traditions of the Torah and the Old Testament. So it keeps connecting to these roots of this shared essence, saying, don't worry, it's all related. It's all in God's hands. It's all in the hands of the divine. And again, I stress that you can, this is why I said you don't have to be religious necessarily. But if you have faith in something in a higher power, that's what it's referencing. You're not completely in charge. As human beings, we only have control over so much. And there's a point where we have to say, okay, it's out of my control. I trust that God, the universe, the greater being, the higher power, is leading this to a certain point. And that's what it's saying, you know?

Leyla: Absolutely. And this, like, you know, the storm, like we're not in charge of like, these storms or sometimes these things just happen.

Sahba: No. Exactly. And I think that's what, in our modern-day world, at least for me, I struggle with a lot. You’re constantly like, you feel like you should be, you have to control it somehow. And yes, of course, we have responsibilities, and we have duties that we must meet. But it doesn't mean, you know, just don't care about anything, but it does mean that know your limits.

Leyla: Yes. And he's not saying don't do anything. He's just saying, “gham makhor!” Don't let sorrow overtake you.

Sahba: Exactly, exactly. Yeah. Don't be engulfed like you said yourself. Don't be engulfed by sorrow. I'm getting excited.

Leyla: Yeah, of course, yeah, that's the sign of a good poem. It's so exciting.

Sahba: Exactly, exactly. Imagine he wrote this in the 14th century, and we still read it today. And it affects our heart in this way. You know, it's truly magnificent.

Leyla: Magnificent, yes!

Sahba: dar beeyābān gar bé shoghé ka'bé khāhee zad ghadam. So in the desert, if out of longing for, desire for the “ka'bé,” ‘the House of God,’ you walk. So if you're traversing the desert, you know, if you're going through difficulty out of longing for the House of the Creator, in a way to encounter the Creator to the greatest way possible in this world, which is to visit his home, his house, and that's the closest you can get essentially, in this world to God, is to visit his house, the “ka'bé.” So if out of the desire to visit the House of God, you traverse this desert, the desert, you traverse these difficulties and these hardships. sarzanesh-hā gar konad khāré moghaylān, gham makhor! Should the, the “khāré moghaylān” is known as ‘the Egyptian thorn’ or ‘the Arabian thorn.’ It's a thorn that's found in the Egyptian and the Arabian deserts. And again, this harkens to the story of Joseph, Egypt, Canaan, all of these areas that are in the same story and in the same region. So should the Egyptian thorn, and that's why I chose to translate it as ‘Egyptian thorn,’ because it's in line with Egypt. And that's where Joseph lives in the story, and so on. So should the Egyptian thorn, should these thorns, should these difficulties that arise in the path, the thorn is a symbol of hardships and difficulties. Should these thorns rebuke you, fear not! And ‘rebuke’ is a strange word. And he uses that “sarzanesh,” should it chastise you, should it torment you, is essentially what he's saying. But also I like the concept of ‘rebuke,’ because in the path of finding your truth or finding, becoming closer to the divine, you're going to meet challenges and people who will often say what are you doing? “beekhodee-yé,” you're wasting your time, all these things. And so he’s saying, don't worry, just follow the path. Keep going. garché manzel bas khatarnāk ast ō maghsad bas ba'eed ‘Although,’ “gar,” “agar,” ‘if,’ “ché,” ‘although,’ “manzel.” So “manzel” in modern Persian we use to mean ‘house.’ But it's literally the place of descent. And what it refers to in this poetry is when the caravans would go on these journeys, they would have multiple “manzels” on the way. They would have places where they would descend to rest in a caravanserai and then get up the next morning and continue on their path. So here it means your stops on the path. So “garché manzel bas khatarnāk ast,” even though these stops each have or each of these portions of your travel is “bas khatarnāk,” ‘is very dangerous,’ has its own dangers, even though every portion of this travel has its own dangers, “va maghsad,” ‘and the destination,’ “bas ba'eed,” ‘and the destination still quite far,’ “heech rāhee neest, k'ān-rā neest pāyān,” ‘there is no path to which there is no end.’

Leyla: That is so beautiful!

Sahba: Isn't it?

Leyla: Yes.

Sahba: Yeah, ‘there is no path that has no end,’ “gham makhor!” ‘Grieve not!’ “heech rāhee neest, k'ān-rā neest pāyān, gham makhor!”

Leyla: Yeah. That is so beautiful!

Sahba: There are so many zingers in here for people to memorize. You can choose so many of these verses to memorize, and they're great.

Leyla: Yeah, that is really wonderful. Such a clear, like, the road is dangerous. It even harkens back to, like, there are these thorns on the way, there are all these dangers, there are all these, but eventually you will reach the destination. I love that.

Sahba: hālé mā dar ferghaté jānān ō ebrāmé ragheeb jomlé meedānad khodāyé hālgardān, gham makhor! So here, now in these last two lines, we get sort of more into the construct or the element, the poetic element of the poem, in which he refers to the common tropes in the ghazal. So obviously, in the ghazal, it's a love lyric. So you have the “jānān,” ‘the beloved,’ and you have the “ragheebs,” you have ‘the competitors,’ those who try to vie for the love of the beloved with you. So they're the thorns in your side, essentially. So he says, ‘our state,’ “hālé mā,” “dar ferghaté jānān,” ‘in separation from the beloved,’ from the “jānān,” “va ebrāmé ragheeb,” and the pushing or the sort of the annoyances of the competitors, of the rivals. So there's a juxtaposition here. And in one sense, he's pining for the beloved, in another, he's getting irritated by the competitors, the rivals. So our state, in separation from the beloved and the vying of the rivals, “jomlé meedānad khodāyé hālgardān.” ‘All of it,’ “jomlé” here is like ‘all of it,’ “meedānad khodāyé hālgardān,” ‘knows the Lord who’ “hālgardān,” and see he's playing with the “hāl” in the first hemistich. All of it is known by the Lord who changes states, who turns your sorrow into joy, who turns your anxiety into peace. The Lord who changes your state. So all of this is known. God knows everything, he's saying. My pining for the beloved and my irritation at these rivals, all of it is known by the state turning, the “hālgardān.” The condition changing Lord, “gham makhor!” ‘Grieve not!’

Leyla: Or “hālgardān” could be the person who controls the state. Yeah, it is very hard to translate, isn't it?

Sahba: It can also be the one who changes the present, because “hāl” can be ‘the present,’ so it's the one who changes the present, but literally it's the one who changes the state of being, the one who changes the conditions. So he can turn your sorrow into joy. He can turn your anxiety into peace. That's the reference. And then we get to the “takhallos.” So the part where the poet refers to himself. “hāfezā,” ‘o Hafez,’ hāfezā, dar konjé faghr ō khelvaté shab-hāyé tār And so this “takhallos” is always the portion where he gives himself advice then, you know, he's like, comes back to himself and says, okay, so ‘o Hafez, in the corner of poverty,’ meaning in the depths of poverty, “dar konjé faghr,” where you've been left alone and ignored by everyone, you're just all alone and deserted in the corner of poverty, “va khelvaté shab-hāyé tār,” ‘and the loneliness of dark nights.’ ‘o Hafez, in the depths of poverty and the loneliness of dark nights,’ “tā bovad,” 'as long as it is,’ “tā bāshad,” “tā bovad verdat do'ā vō dars ghor'ān, gham makhor!” ‘So long as your mantra, that which you keep repeating to yourself, is prayer for the beloved, to God,’ and “va dars ghor'ān,” ‘and your lesson,’ but that which guides you, and ‘your guide, the Qur’an,’ the holy book. So, ‘so long as your mantra is prayer and your guide, the holy book,’ “gham makhor!” ‘Fear not.’ Meaning, so long as you have the higher being on your side, don't worry.

Leyla: Wow. So basically, it's just saying all these things that you cannot control. All these things are happening in the world, it's turning. It's stormy, that you're in the depths of poverty and loneliness, and all this stuff is happening around you. But the thing that you can control is to speak prayer, to speak gratitude, to speak exaltation, and to study. Study and speak gratitude. That's all that you can do. That gives me chills.

Sahba: Isn't it beautiful?

Leyla: That is beautiful!

Sahba: I love because it's, these days, we talk so much about manifestation and mantras and things as if they're like new concepts and they're not. He's referring to this in the 14th century. He's like, control what you can control. And that is communion with the higher being, prayer, study. These are the things that you can do.

Leyla: Absolutely. Wow. That is very, very beautiful.

Sahba: And I love that, you know, it is like a prayer. The “gham makhor!” “gham makhor!” “gham makhor!” It’s this repetition and a prayer and a mantra. So he's giving you the mantra that you should have for this poem as well. āfareen, āfareen. Yes, exactly. Yeah, yeah. I love it. Is there any music that you know, has Shajarian or anyone done a song on this one? I'm sure they have. I can't think of any off the top of my head, but I'm sure they have. Yeah.

Leyla: We'll look at this, so can you tell me what does this, going back to the bibliomancy, what does this say to you? If you were to get this poem right now, in this state that you're in.

Sahba: This is one of the easiest poems to interpret. The thing with Hafez’s bibliomancy for me is like, I'm open. I'm like, oh God, what is it? I don't know how to interpret this for anyone. And maybe that's because I'm not a skilled fortuneteller, but this one's clear. You know, it's saying whatever you're worried about. Don't worry. It's going to be okay. But it's also saying trust. Trust the process. Trust in the higher source. Trust that whatever is in your best interest is going to happen. I think actually, that's more than anything. It's not just like, don't worry, be happy. It's saying trust.

Leyla: Yes, and that you don't know what the greater meaning is.

Sahba: You don’t know. Exactly, exactly.

Leyla: The only thing that you know is this prayer and this study.

Sahba: Yeah, yeah. Control what you can. That’s it.

Leyla: Wonderful. And what would you say the shāh beyt, we talked about the shāh beyt, what is the shāh beyt for this poem?

Sahba: I think the shāh beyt for this poem is probably the opening line. It’s “yoosofé gom gashté bāz āyad bé kan'ān, gham makhor! kolbéyé ahzān shavad roozee golestān, gham makhor!” I think that’s the shāh beyt.

Leyla: Okay. Is it up for interpretation?

Sahba: The line itself?

Leyla: What the shāh beyt would be, like could somebody else read it and say-

Sahba: Sure. I'm sure, definitely, I mean, I'm in no way, I don't want to pretend to be a Hafez-shenās. I'm sure the Hafez-shenāses will tell you maybe it's something else, but from my experience, I think the shāh beyt is the first line, because that's the line that also everyone knows. The reason I actually think it's the shāh beyt is not because everyone knows it, but it's because it's the line that encompasses within itself the entirety of the poem and the entirety of the imagery that's used in the poem. Because the poem keeps harkening to these images from the Old Testament and the Qur’an. And that line in itself covers a whole story. Because it talks about yoosof, it talks about kan’ān, it talks about his return, it talks about “kolbéyé ahzān,” and the whole concept of trusting, “gham makhor!”

Leyla: Yes. And to see, so Jacob was the embodiment of that. He was in his sorrow. But then, eventually, the road had an end, and it had a happy ending for him.

Sahba: Yeah, exactly.

Leyla: And just to go back, I didn't explain. “shāh beyt” is the king line that, “shāh” is ‘king.’ And so it's the master line of a poem that usually you read, and you go ‘ah!’ I think for me, the line that I kind of ‘ah’ was the line about the road. I found that really.

Sahba: Yeah. I think that was for you. Yeah. Yeah. I could tell.

Leyla: That was the one that took my breath away. Although I mean, all of it by the end, like you said, it weaves together pearls, and by the end, you're like, I totally understand what you're saying. I know what I need to do right now. I'm inspired. Let's go.

Sahba: Yeah, I think there are a lot of lines that I was saying, there are the zingers, and it's like the fourth line too. “doré gardoon gar dō roozee bar morādé mā naraft dā'eman yeksān nabāshad hālé dorān, gham makhor!” I think that one is quite beautiful.

Leyla: Yeah, that is really perfect.

Sahba: So is the one about the flood, and Noah being the captain, all of these I think.

Leyla: Absolutely. You're right. So there's a lot to choose from from here. So what we're going to require for this poem, so generally, someone in Iran would have this whole thing memorized from the very beginning to the very end because there's so much in here. So I would encourage our listeners to memorize the whole thing actually, again, even if you're a complete beginner to the Persian language, we're going to have five more lessons where we're going to go over this word by word so that by the end you're going to hear these lines, and it's no longer going to sound foreign to you, which is very exciting when it happens. The poems are always the hardest thing to convince the students to get into, but in the end, it's always the most rewarding part of it. But also, if it's your first time or something and you want to just memorize two of them that speak most to you, two lines that speak the most to you, that will also be totally fine. But there's also a game that they play in Iran, for example, where the last letter of the poem, they have to then recite another entire ghazal that starts with that letter. So in this case, it would be the “ré” from the”gham makhor!” And then someone would jump in and just hop in with some ghazal that starts with a “ré.” Which, Sahba, do you know one off the top of your head?

Sahba: No, I'm not good at “moshā'eré.” No, don't put me on the spot.

Leyla: Okay. Wonderful. So thank you! This was an amazing poem, amazing selection. When I first glanced through it, I didn't see the vision, but now I completely get it. And that's the beauty of reading these in their original language and really going over it in depth like we do, is that you really understand it. And even a phrase like “gham makhor,” it's amazing how in translation we can talk about it for ten minutes, which I think we did. This is a long poetry lesson, but thank you so much, Sahba jān, for being with us on this journey, for taking us on this journey.

Sahba: My pleasure. I look forward to sharing our student videos with you when we have them. I'm excited. When I was picking this poem, I was like, this one's a good one. They have a lot of lines to pick from if they don’t want to memorize the whole thing, which they should.

Leyla: And in this point of our time in our history, I think that everyone can use this phrase of “gham makhor,” and just really hold that as a mantra. “gham makhor,” “gham makhor,” we will get through this. There will be an end to this road.

Sahba: Absolutely.

Leyla: Thank you, sahbā jān. And until next time, bé omeedé deedār from leylā.

Sahba: bé omeedé deedār. khodāhāfez.